These days, witnessing a theater company staging a live, in-person production with as much skill and heart as GableStage demonstrates in its season opener is, in a word, priceless.

Surely, the late Joseph Adler, the company’s producing artistic director for 20 years, and a multi award-winning South Florida theater legend, would have been proud of the onstage product. Specifically, it is an intense, believable, captivating, and, at times, humorous production of Arthur Miller’s engrossing classic drama, The Price.

This riveting production marked Adler’s last directorial effort before his passing last spring from a long illness. New GableStage Producing Artistic Director, Bari Newport, used Adler’s notes to direct the production. In fact, it is a “marriage of Joe’s vision and my own,” Newport wrote in the program.

The production, which GableStage has dedicated to Adler, opened on Saturday night. It runs through Dec. 12 in the professional, nonprofit company’s intimate playing space next to the Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables.

While many might be familiar with Miller (1915-2005) from plays such as his 1949 Pulitzer Prize-winning drama, Death of a Salesman, The Price has also experienced wide success. In particular, the play, written in 1967, and set in 1968, the same year in which it premiered on Broadway, has experienced four Broadway revivals. The piece was nominated for two 1968 Tony Awards. They included a nomination for “Best Play.”

The Price is a meaty, compelling, thought-provoking, and realistic piece. It takes place on the attic floor of a Manhattan Brownstone apartment building in 1968. As is true with many Miller plays, The Price focuses on relationships between family members.

In The Price, which runs more than two hours, law enforcement officer Victor Franz, nearing 50, is approaching retirement. He gave up pursuing an education in science and a career in that field to help his father survive the Great Depression, and deal with his mother’s death. Meanwhile, Victor’s brother, Walter, became a successful doctor, refusing to sacrifice his career for dad.

As the play begins, the brothers have not spoken to each other since their father’s death 16 years earlier. They meet in an upstairs attic of what was once their father’s home to sell the many antiques the older man collected. Victor’s wife, Esther, is also present. So, too, is 89-year-old second-hand furniture dealer, Gregory Solomon.

That, essentially, is the plot. In lesser hands, The Price might have suffered from stasis. Indeed, the play might have amounted to essentially an “auction” between the brothers, with Solomon serving as auctioneer.

Instead, The Price is a gripping and layered piece of theater that covers multiple themes without feeling overstuffed or unfocused. For instance, Miller focuses not only on the price of furniture, but the price of one’s decisions. Also, the play touches on themes such as guilt, regret, familial duty, the way we attach emotion to material objects, family dynamics, the unreliability of memory, and how we use illusion to hide from reality.

Events such as memorials and the sale of objects belonging to someone who has died, especially family members, are often ripe times for long bottled-up emotions and feelings to come pouring out. That happens in The Price, a play in which Miller achieves balance. Specifically, the playwright, without condemning or praising either sibling for their past actions, allows them to fully state their viewpoints. In the end, it is hard for us to label either sibling as simply “right” or “wrong.” Instead, the play makes us think and look inward, as quality works usually do.

As we look onstage, we see scenic designer Lyle Baskin’s visually pleasing depiction of the attic, lit realistically by lighting designer Tony Galaska. Due to the pandemic, the set has remained onstage for 19 months, waiting to come to life.

The set is spacious. And, we get a clear sense of just how many things the siblings’ father collected. From Baskin’s set, it becomes clear that the father and his sons took pride in the collection. The men did not carelessly bunch items on top of each other, leaving a giant mess. Among other things, we see piles of books, rolled up carpets, and an old Victrola. Meanwhile, a fancy-looking chandelier, as part of the home’s furniture, lends the place an elegant aura. However, workers are about to tear down the deteriorating apartment building. Perhaps Miller included this fact to symbolize or foreshadow the falling apart of this family.

Newport, based on Adler’s vision, slowly builds intensity. Actually, the build-up to the highly charged scenes toward the play’s end takes a while.

The entire first act, which lasts about an hour, is quite comical. It features the antics of Solomon, who interacts with Victor and his wife, Esther, as they try to arrive at a mutually agreed-upon selling price.

Solomon sometimes seems like a comic creation belonging in another playwright’s work, perhaps Neil Simon’s. We learn that this Jewish-Russian man served in the British Navy, comes from a family of acrobats, and is one himself. Miller could have axed these and other facts, while still retaining the essence of The Price. Other things that we learn about Solomon keep this character from becoming a caricature. For instance, his daughter’s suicide haunts him.

As Solomon, Peter Haig, who alternates in the role with George Schiavone, creates a delightfully comic character. He injects Solomon with just enough humanity to prevent him from becoming a caricature. Also, to his credit, Haig never appears to beg for laughs, while demonstrating deft comic timing. Haig speaks in a sing-song type voice that sounds scratchy at times. In appearance and sound, Haig’s Solomon, at times a curmudgeon, looks and sounds like a cross between a transformed Ebenezer Scrooge and King Lear. The actor sports a long, black coat and a large black hat, part of costume designer Emil White’s character-defining clothes.

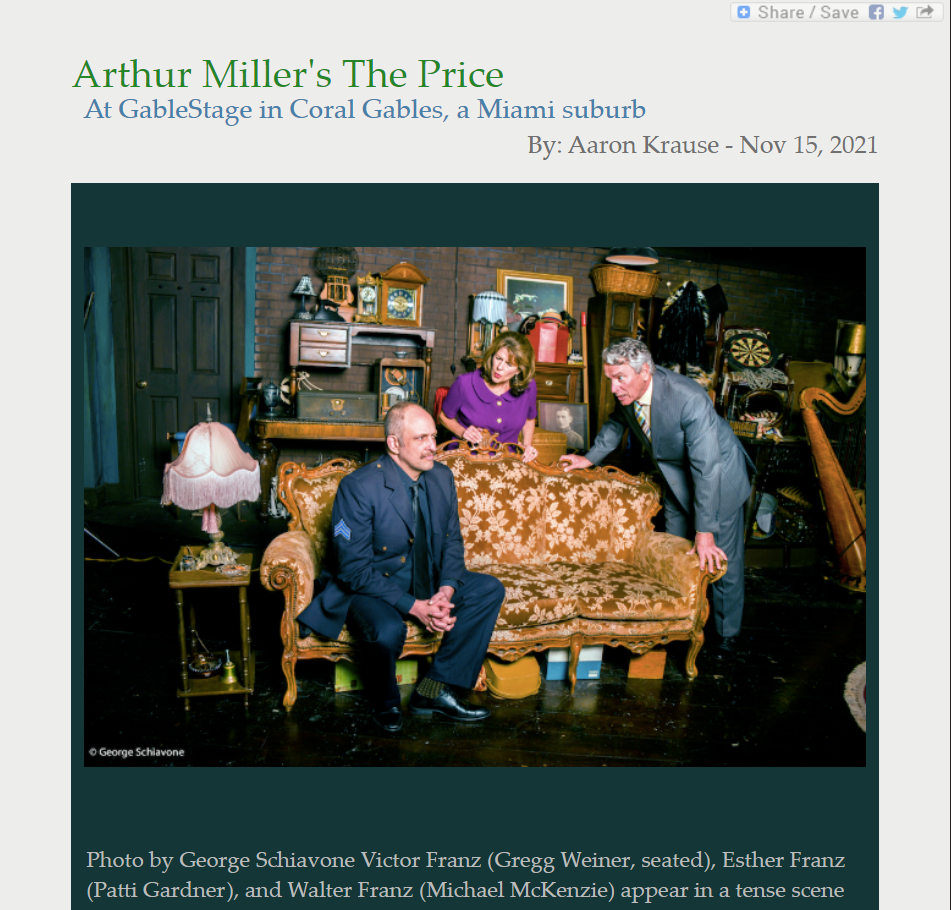

While Victor Franz is not a particularly likable person, Gregg Weiner, in the role, makes it clear that Victor sincerely loves his wife. Newport, through Adler’s vision, places the two in positions that clearly communicate their closeness.

Weiner imbues Victor with a jaded and impatient aura. He is the type of person who has seen a lot on the police force and clearly has no patience for Solomon’s antics. Later on, a finger-wagging, forceful Weiner projects conviction as he stands up for what he did in the past and grows angry with his brother.

Opposite Weiner’s Victor, Michael McKenzie, when he first appears onstage, conveys an energetic, lively, and happy air as Walter. But when the siblings’ past comes up, and Victor begins accusing Walter of things, McKenzie’s Walter becomes a fiercely defensive man who vehemently stands by his past actions.

In the middle of the two stands Esther Franz. She is a woman who wants something more from life than what her husband has been able to give her.

Patti Gardner skillfully portrays Esther as an assertive, high-strung woman. Through Gardner’s performance, we keenly sense the character’s desperation and frustration. But Esther, like the other characters, are not one-dimensional. While she can be impatient, she has a zest for life. She can be playful and loving toward her husband, which Gardner deftly conveys. Her devotion to her husband is part of what endears us to Esther.

It is a testament to the actors’ skill that they forcefully play these characters without making their acting look forced.

Miller, who was a prolific playwright, demonstrated a keen concern for the plight of the common man in his plays. These vastly talented cast members, who utter each word as though they’re saying it for the first time, inject their characters with believable humanity. As a result, we can identify with them, and perhaps recognize people we know in them.

For those who regularly witness GableStage’s shows, a Joe Adler-directed production is easy to recognize. It is seamless — just like this production of The Price.